A US Deep Sea Mining Glossary

In case you need it

Deep sea mining is an inherently complicated issue. But it’s perhaps especially complicated in the US, where (it often seems) everything is complicated. In this country, deep sea mining brings together various government agencies, obscure laws, and international partnerships (and conflicts).

So, now that the US is formally and openly moving this industry forward, I wanted to make a reference guide to the terms you might encounter.

Some readers here are deep sea mining experts, and might not need this list. But for those just learning about it, consider this your US deep sea mining dictionary.

My goal is to make understanding deep sea mining as easy, painless, and interesting as possible. So, if there are terms you’d like added to the list, other glossaries you’d like to see, or questions I can help answer, feel free to comment or reply anytime. I’ve included the basics for now, and will keep this list updated with new terms and names as they come up.

Allseas

An offshore technology brand that has partnered with deep sea miners. It owns and operates the Hidden Gem, a deep sea mining ship.

Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ)

The formal term for the international seabed, beyond any country’s borders.

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)

A US agency within the Department of the Interior. BOEM is in charge of US offshore resources, including issuing licenses to mine the US seabed. Its stated mission is “to manage development of US Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) energy, mineral, and geological resources in an environmentally and economically responsible way.”

Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ)

A large section of seabed in the international Pacific, between Hawaii and Mexico, where seabed minerals are abundant. Many deep sea miners are exploring the mineral resources there, through international permits.

Deep Reach Technology

An offshore engineering company that works on deep sea mining projects with various clients.

Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA)

A law passed in 1980, which allows the US to issue permits for deep sea mining in international waters. It was originally intended as a temporary law, so US companies could explore mining the international seabed, until international rules were in place. However, the US never agreed to the international deep sea mining rules, so DSHMRA still exists.

Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

The section of ocean off a country’s coast which that country controls, generally extending 200 nautical miles offshore. Each country has exclusive rights to the resources (like seafood or minerals) found in its EEZ.

Executive Order

A written directive signed by the US president, which tells the government what to do. In 2025, President Trump signed an executive order on deep sea mining called “Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources”. This order outlines steps for fast-tracking a new US deep sea mining industry, such as speeding up permitting.

Exploration

The term for any deep sea mining activities aside from commercial extraction (which has never yet been permitted anywhere in the world). Exploration can include finding minerals, researching ecosystems, and mining at test scale.

Extended Continental Shelf (ECS)

Continental shelf that extends past 200 nautical miles offshore. If a country can prove its continental shelf extends this far, it can claim control of the seabed on that shelf (although not the waters above). In effect, this extends a country’s offshore borders. The US has a large ECS area, which it expanded in 2023.

Ferromanganese Crust

A layer of minerals that naturally forms on seabed formations, such as rocks and mountains, over millions of years. A ferromanganese crust is mainly iron (ferro means “contains iron”) and manganese. Different crusts can have different mineral compositions, so you may also see the terms “manganese crust” or “cobalt-rich ferromanganese crust.” While it’s technologically challenging, some deep sea miners aim to strip these crusts for their minerals.

Global Sea Mineral Resources (GSR)

A Belgian deep sea mining company which also builds mining machines used by other companies.

Impossible Metals

A US deep sea mining company headquartered in San Jose, California. The company designs its own deep sea mining machines. These machines are meant to selectively pluck minerals from the seabed, avoiding minerals with large marine life (like corals) on them. Impossible Metals is currently seeking permits, through BOEM, for mining the seabed around American Samoa.

International Seabed Authority (ISA)

An intergovernmental organization formed in 1982, which became active in 1994. Headquartered in Jamaica, it oversees deep sea mining in international waters. The ISA has issued many permits to explore deep sea minerals, but has never yet issued permits to mine those minerals. That’s because it hasn’t yet finished its mining regulations, which must be decided on by ISA member countries. Most countries in the world are ISA members, but not the US.

Lockheed Martin

A large US defense company, which mainly manufactures aircraft and other military equipment. It holds two deep sea mining exploration licenses for the international seabed, first issued through DSHMRA in 1984. The licenses are valid until 2027 and can also be extended. It’s unclear whether Lockheed Martin intends to move forward with any deep sea mining plans. Minerals found in the deep sea can be used for building weapons and defense technology.

Merchant Marine Act

A law passed in 1920, which includes regulations for US maritime commerce. One section, called the Jones Act, requires that goods transported between US ports be on ships that are US built, owned, and crewed. These rules could impact deep sea mining companies hoping to bring minerals to the US, as some are using ships built, owned, and crewed by other nations. Jones Act exemptions can be made in the “interest of national defense.” While deep sea minerals could become components of weapons and other defense products, it’s not clear whether they’d qualify for an exemption.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

A US agency within the Department of Commerce. Through DSHMRA, NOAA is in charge of issuing US licenses to mine the international seabed. While it’s best-known as an agency that researches oceans, weather, coastlines, and climate, part of its stated mission is “to conserve and manage coastal and marine ecosystems and resources.”

Ocean Minerals

A US deep sea mining company. Its subsidiary, Moana Minerals, is based in the Cook Islands and explores deep sea mining there.

Odyssey Marine Exploration

A US deep sea exploration company that started with finding shipwrecks, but has switched to marine minerals. The company focuses on technology and research to locate and explore seabed minerals. Ocean Minerals is one of its partners.

Orpheus Ocean

A US company that builds robotics for deep sea research. While the brand isn’t focused solely on minerals, its technology may help deep sea miners do research more quickly and effectively.

Outer Continental Shelf (OCS)

The seafloor within US control, but beyond US state and territory waters.

Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA)

A law passed in 1953 that defined the US OCS. It also put the Department of the Interior in charge of mineral exploration and extraction on the shelf, with the power to issue licenses for that exploration and extraction.

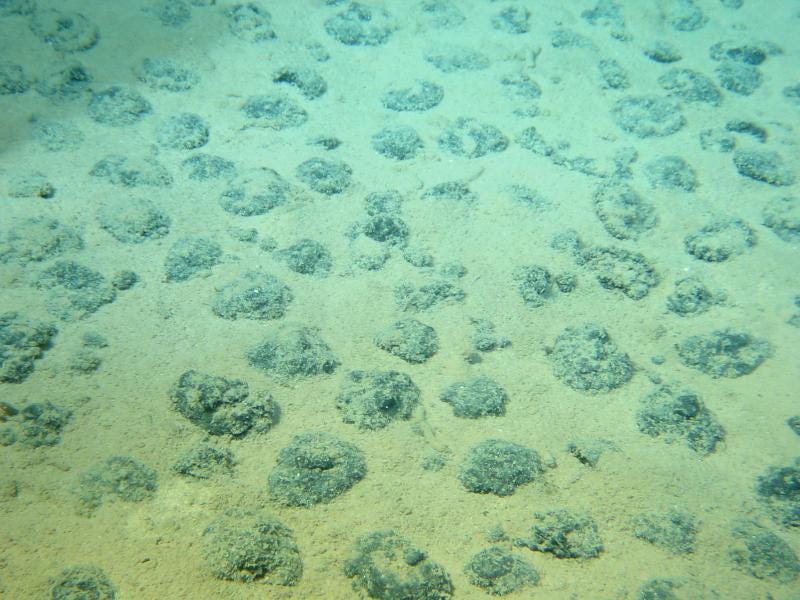

Polymetallic Nodule

A rock-like clump of minerals that naturally forms on the seafloor over millions of years. Found worldwide, both in national waters and on the international seabed, these nodules are an integral part of the deep sea habitat. Most deep sea miners are interested in polymetallic nodules, the most accessible and common type of deep sea mineral formation. Because they aren’t buried, they can be mined without digging deep. May also be called manganese nodules or ferromanganese nodules.

Seafloor Massive Sulfide (SMS)

A mineral-rich hydrothermal vent. These form as seawater becomes heated by magma in Earth’s crust, then carries and deposits minerals at the vent site. While super-hot active vents are impractical to mine, some deep sea miners are interested in removing inactive vents for their minerals. As deep sea habitats, these sites are relatively rare and haven’t been well-researched yet.

The Metals Company (TMC)

A Canadian deep sea mining company, which operates in other countries by opening subsidiaries in them. Its US subsidiary is in Raleigh, North Carolina. The company plans to use large vacuum-like robots, called “crawlers,” to suck polymetallic nodules off the seafloor. It also works with Allseas to develop mining equipment, and uses the Allseas ship Hidden Gem. TMC has applied for US permits, through NOAA/DSHMRA, to explore and mine minerals from the international seabed.

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

The international treaty that legally governs activities at sea, which was launched in 1982 and came into effect in 1994. It covers everything from rights in territorial seas to actions in international waters. (The ISA was also established through UNCLOS.) Because of this treaty, the high seas are no longer lawless. Countries can’t simply go to the international ocean and do whatever they want (dump trash, for example). Although it typically follows the rules of UNCLOS, the US has never formally agreed to the treaty.

United States Geological Survey (USGS)

A US agency within the Department of the Interior. This agency researches geology, biology, and more, and “provides science for a changing world, which reflects and responds to society’s continuously evolving needs.” Through efforts like the Global Marine Mineral Resources project, it maps and quantifies seabed mineral deposits.

The astute reader will notice that I first published this list slightly out of alphabetical order! It has been corrected.