How the World’s Weirdest Snail Became Endangered

Mining threatens this mighty mollusk

“World’s weirdest snail” is a bold claim, in a world that has psychedelic flamingo tongue snails and fish-hunting cone snails. But the scaly-foot deserves the title.

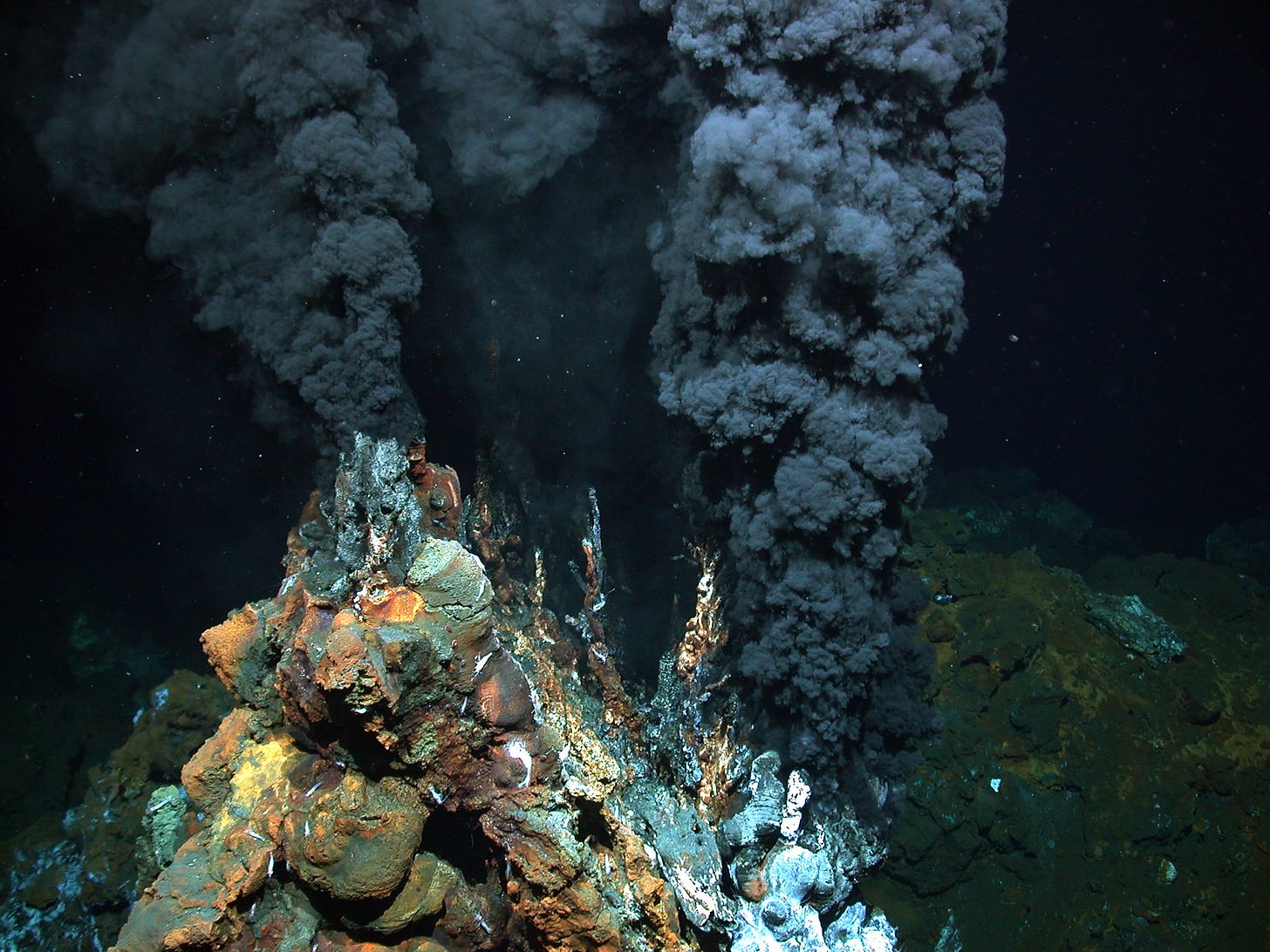

This wonderful marine weirdo has the animal kingdom’s biggest heart (relative to body size, of course: the snail itself is quite small). Because it lives more than a mile below the ocean’s surface, where there’s hardly any oxygen, it relies on this massive heart to keep oxygen pumping around its body. Stranger yet, its shell is made of iron. Scientists think microbes help the snails build super-strong shells from the vent fluid’s iron sulfides. Like collectible toys, the snails come in a range of colors, caused by variations in the vent fluid used to build their shells. Microbes in each snail also provide it with food by turning vent chemicals into energy.

But perhaps strangest of all is its namesake – the armor-like scales on its exposed foot, made of calcium carbonate under iron sulfides.

You’d think a creature so tough and well-prepared would have few things to worry about. But in 2019, it was declared endangered: the first species officially endangered by deep sea mining.

Even though this mining hasn’t begun at scale yet, the scaly-foot snail lives in such specific areas that each snail population could be wiped out by a single expedition. Though we know little about this species – its larval form, for example, remains a mystery – we could lose it before ever learning more. The snail’s habitat is limited to hydrothermal vents in just a few parts of the Indian Ocean, as far as we can tell. Those vents, made of valuable materials like gold and copper, are among the targets of deep sea miners.

The International Seabed Authority has pushed its mining-regulations deadline to 2025. Still, before commercial deep sea mining is permitted, exploratory mining could render the scaly-foot extinct. There’s also the risk that mining companies will be able to exploit a legal loophole to get early commercial permits.

Deep sea mining involves a tangled web of secretive investors, big money, and unequal partnerships between Pacific countries and private companies, which leave most of the profits to the companies. A short list of people stands to make a lot of money from wide swaths of ocean destruction. The International Seabed Authority itself appears to favor profits over environmental protections: secretary-general Michael Lodge calls deep sea mining “the slowest gold rush in history.” (If you’re up for a long read, here’s a valiant effort to unpack deep sea mining’s major funders and power players. Feel free to drop me a line if the paywall is an issue.)

Yet in spite of what’s at stake, I find myself struggling to pay attention to the people in this story. Their actions seem almost mechanical: a quest for money, resources, and power that I can’t really relate to. I feel more aligned with the scaly-foot snail. Like me, it’s just another strange little creature trying to survive in a world that’s often threatening in ways beyond comprehension. What else is there to do but put on armor and keep going?

Well done, Elyse!