How to Save the Moon

Deep sea mining decisions could shape lunar mining’s future

Fire. Aether. A glowing deity. Land and seas like Earth. These are what people once thought the moon was made of.

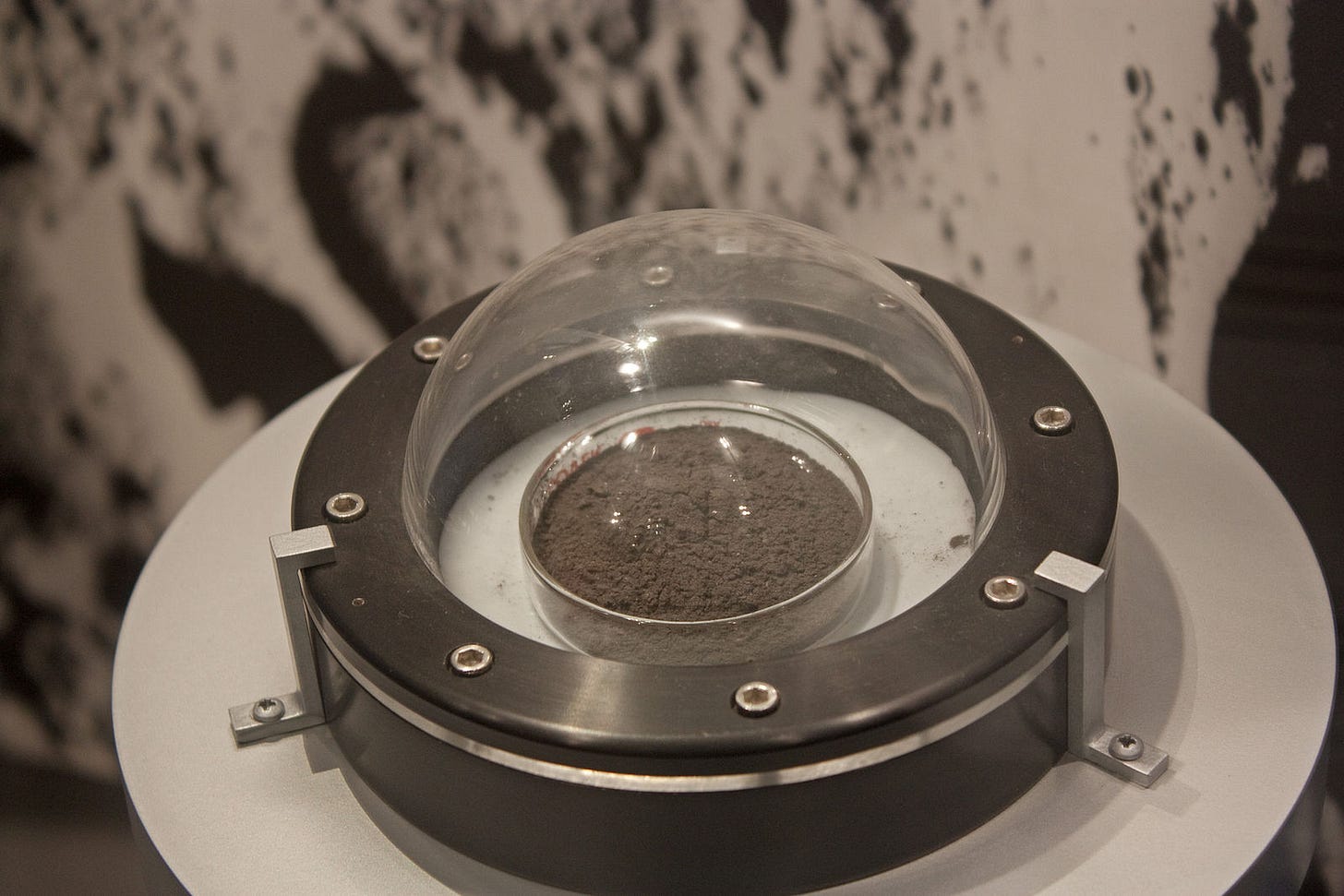

Today, we know the moon’s made of simpler stuff. Its surface is a layer of rocks and dust called lunar regolith. It has metals, minerals, and gases, like iron, calcium, and helium. It even has water, though it’s always frozen. Through research and sampling, science has brought our knowledge of that great celestial pearl down to Earth. The moon is an item, smaller than the Pacific Ocean, rocky, measurable. Divisible into component parts.

These simple moon materials can be useful, too. Humans have long harvested minerals, metals, and gases from Earth. Now, as Earth’s natural resources become depleted, certain powers have begun to look skyward. Moon mining is their new ambition.

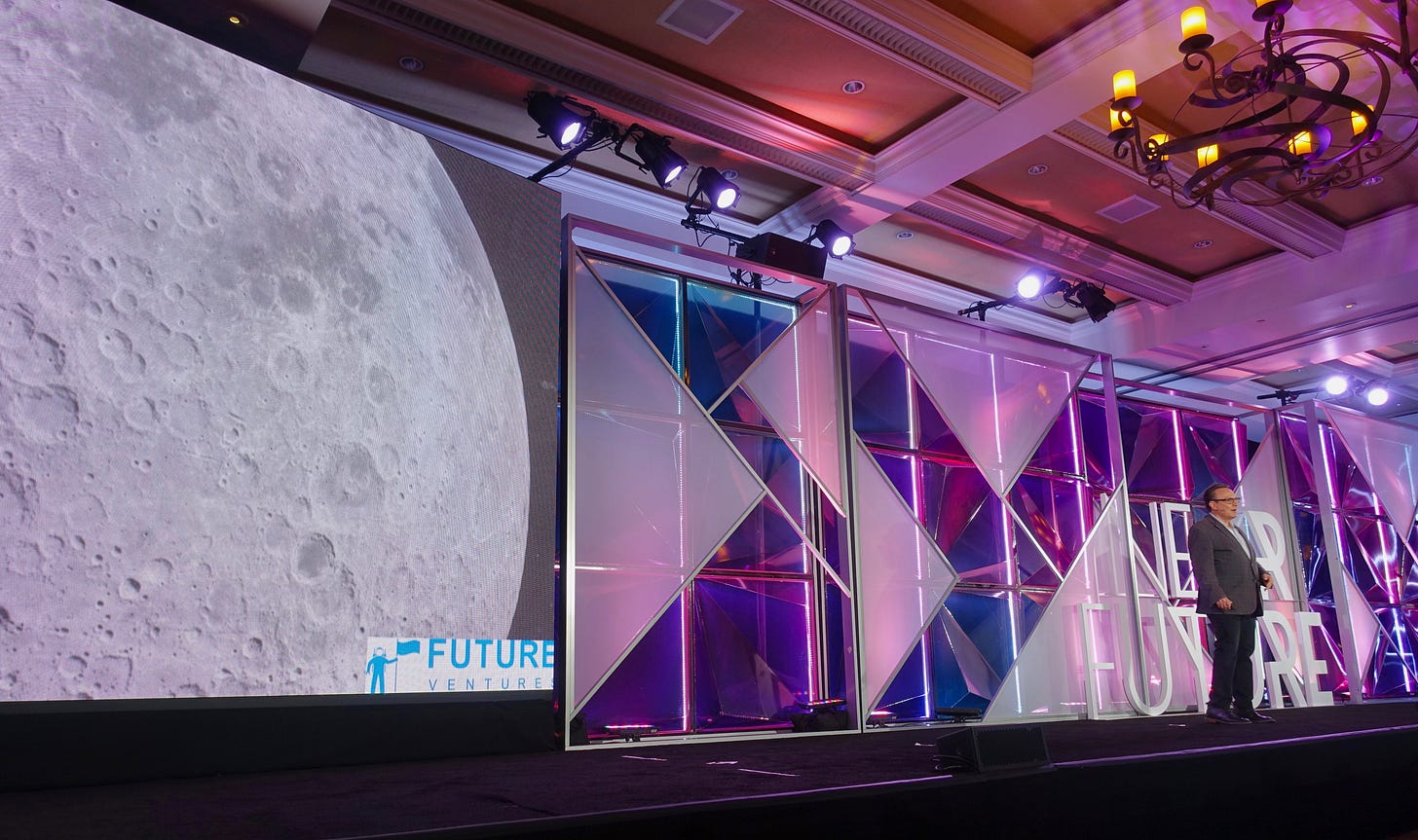

While lunar mining has long appeared in science fiction, top scientists and well-funded companies are working to make it a reality. The prospect is closer than you might think.

In the US, the law already ensures private companies will own what they mine from the moon. (Though, of course, some may argue that no one should have ownership over pieces of a celestial body.) Startups with names like Interlune have raised millions to build mining technology that will let them cash in. Interlune plans to mine a type of helium, scarce on Earth but common on the moon, to fuel quantum computers and nuclear fusion reactors. Lunar rare earth metals could also be used to build everyday technologies, like smartphones.

Sound familiar? Like deep sea mining, moon mining is an ambitious, high-tech proposed way to get materials for modern technology. Once the realm of science fiction, it’s suddenly a serious possibility. Lunar mining regulations would likely be modeled on deep sea mining regulations, which are currently being forged by the International Seabed Authority.

As with deep sea mining, companies and governments are aligned in the push for moon mining. The US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is working to make lunar mining a reality. NASA’s ambitions include a permanent lunar base, where mined resources would support astronauts living on the moon, and their expeditions farther into the solar system. The remarkable feat of placing human feet on that distant orb, it seems, is not enough. Other countries are also racing for the chance to pioneer the nascent industry: Russia and China are among the global powers with moon mining ambitions.

In this era, for the first time, the world is deciding how to divvy up resources from places no country owns: the deepest seabed, asteroids, the moon.

These efforts are possible because we live in a high-tech age, one of robotics and AI and instant global communication. The sci fi world is already here. But given the high and growing cost of its technological ambitions, it’s worth asking whether this is the sci fi world we want.

Like the deep sea, the moon is a global commons, shared by everyone. Both moon and ocean shape life on Earth. The prospect of moon mining, like the prospect of deep sea mining, is thus an invitation to make a globe-spanning decision.

We must decide, collectively, whether this mining fits into our ideal future: all people of the world deserve a say. The resources of the moon and deep sea are formally considered part of the “common heritage of humanity.” This is often interpreted to mean that their resources should be used in a way that benefits everyone, financially or otherwise. Yet left intact, the moon and deep sea are resources of a sort, too. Wholes that may be greater than the sum of their parts.

Here on Earth, resource extraction is already fraught. Modern mining threatens workers’ lives and devastates ecosystems, from mountainsides to more coastal seabeds. As digital technology has proliferated, the mining to build it has ramped up. Some are already questioning whether the tradeoffs are worth it.

But lunar mining puts this issue (almost literally) in a vacuum. There are no ecosystems there to devastate. It would be done by robots, not human workers. Its impacts would be far from any homes.

Maybe, though, it is through this vacuum that we can look at resource extraction with clear eyes. With no ecological arguments against moon mining, we can unpack the idealistic arguments that lay behind them.

Though it wouldn’t damage living things, lunar mining still has sustainability issues. The moon is big, but its resources aren’t renewable. If mined they will, at some point, run out. Moon mining would also create pollution: space junk too expensive or impractical to clean up. Existing junk in orbit, on Mars, and on the moon is already a strange new environmental issue. Lunar mining would only ramp it up.

Moon mining would also damage a great cultural site. Already, countless cultural sites have been decimated by mining on Earth. The moon is, in a way, the ultimate sacred place: symbolic and significant around the world, from prehistory to the present day. This calls for protection, just as Earth’s sacred places do. Otherwise, the impacts of lunar mining might even be visible to us when we look at the night sky.

And this mining risks robbing us of a longstanding sense of awe. A moon stripped and altered loses some of its inspiring power. The more pieces of moon we remove, the more mundane it may start to seem. This could normalize the extremes of extraction, dulling resistance to mining in other remote and remarkable places: the volcanic seabed, the Arctic, the Antarctic. But by leaving the moon in the sky, we can maintain its full power. We can remind ourselves that just because it can be taken doesn’t mean it should.

A resistance to lunar mining could even unveil a path to a much-needed reckoning with resource use on Earth. Many people and cultures still live with a light footprint. But there are places where resources and energy are consumed far too heavily. Stemming the flow of raw materials may help restructure those lifestyles. What if the same money and scientific effort were put toward recycling on Earth instead of mining the deep sea or the moon? What if old, lasting, and repairable technology became trendier than the new, short-lived, and disposable?

This is an invitation to imagine what else is possible.

Of course, lunar mining may never materialize. Maybe it’ll prove too expensive. Maybe our growing Earthbound issues will distract from the effort.

Still, we can gain necessary wisdom from facing the prospect with care. In this fast-paced era, to pause and reflect is itself a radical act – one which the moon invites us to every night. Through this work of pausing and reflecting, we can reawaken to the moon’s true value.

It provides a stable, rocky foundation for our cultures and calendars. At the same time, its remote mysteriousness also teases at the edges of our consciousness, inspiring us when we turn our eyes to it. Memories bathe in moonlight. Seas pulse with tides. Lunar cycles mark life’s passage.

We have a chance now to preserve this place, for all it’s done for us, and all it has left to do. That’s a lunar lesson we can take back to Earth.