The Deepest Secrets

Coral and capitalism in the shadows

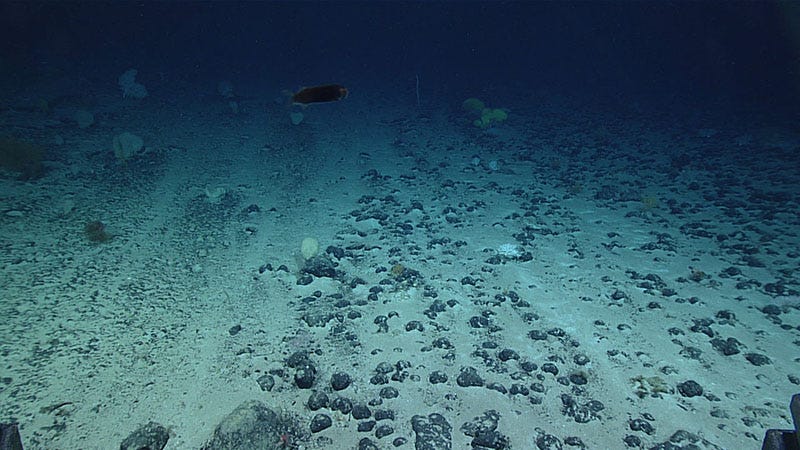

Coral reefs are poster children for tropical seas. But coral’s actually everywhere, from sunny shallows to frigid Arctic depths. In fact, there are more coral reefs in the deep sea than in the tropics. And no matter where they’re found, coral reefs support whole ecosystems, like a city where even the buildings are alive.

In the Atlantic, near the southern US coast, scientists recently discovered the world’s largest-known deep sea coral reef. It covers an area some three times bigger than Yellowstone National Park. Unlike Yellowstone, though, the reef has no official protection from human activities.

It wasn’t surprising to find coral there – but no one expected a reef of this size, until modern 3D mapping revealed it. In fact, it’s entirely possible that there are even bigger coral reefs in the deep sea (not to mention species and ecosystems we’ve never seen before). This reef lies far below the reach of sunlight, in the cold, mysterious depths, evidence of how much we have left to learn on our home planet.

It's also right next to the world’s very first deep sea mining test site, as deep sea ecologist Dr. Andrew Thaler has pointed out. The Blake Plateau, the seabed formation where the reef grows, is rich in minerals as well as coral. In 1970, when deep sea mining was tested there, no one knew they were right beside the world’s biggest deep coral ecosystem. Had mining moved beyond the test phase then, there might have been no reef left to discover.

As it happened, deep sea mining never really moved forward in US waters. But lately the US seems to have a really weird relationship with it. It’s flirting with the idea, I’d say, but without the boldness to make a public statement.

As an example, the US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has an entire website section devoted to “offshore critical mineral resources.” (BOEM also partly funded the study that discovered the coral reef.) “Domestic production of critical minerals will assure a resilient supply chain and represents a potential revenue source for the US Government,” it says, giving what sounds like an endorsement of deep sea mining. A Looking Ahead section details the plans to find and measure US seabed mineral deposits.

The weird part is that no one in the US government (including a State Department representative I interviewed late last year) seems willing to say outright that the country is considering mining its seabed. Yet clicking through government websites and documents increasingly suggests that’s the case. The information is publicly available. But it comes in forms like quiet press releases and sections of lengthy documents. It’s really easy to miss.

Claiming the Continental Shelf

Just before Christmas, the US government added 385,000 square miles to its continental shelf, in a discreet move largely overshadowed by the holidays. Now, the country claims new control over a large wedge of Arctic seafloor, as well as areas beneat…

I recently learned that cobalt, one of the minerals found on the seabed, is used in heat-resistant alloys for military products: things like jet engines and munitions. This goes far toward explaining the US interest in seabed mining. And I don’t think the discovery of a remarkable coral reef, tens of thousands of years in the making, is going to slow that interest at all.

Relatedly, I’ve been thinking about deep time a lot. Deep time is the term for the actual age of Earth: the millions and billions of years that precede you and me. The time that allowed oceans to form, corals to evolve, and polymetallic nodules to grow, as minerals in seawater slowly clung to pieces of ocean debris. These nodules, which deep sea miners want for their minerals, are in fact millions of years old.

What does it mean to take something millions of years in the making – a physical surface that animals have evolved to live on – out of the ocean, and turn it into parts for an iPhone or a jet engine? It’s a question for the philosophers, I suppose. Something to do with where we draw the line between natural and unnatural, or how humans make priorities. But it’s worth pondering.

I hope, as the US dives into yet another chaotic year, that more people will take the time to ponder it.